Badvertising: Polluting Our Minds and Fuelling Climate Chaos by Andrew Simms

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I bought this after watching a cracking podcast by the two authors, one of whom I remembered from the ‘infinite hamster’ animation – a truly disturbing thought experiment about exponential growth.

The book’s basic premise is this: in a free country, unless some object is out-and-out destructive and has no other use, for the most part you can’t get up and outright ban it. What you can do, if you want a lot less of it about, is prevent it being advertised.

But would that make any difference? For us jaded people who’ve seen it all before, adverts don’t really work, right?

Well, apparently they do – and the first two chapters descibe exactly how, citing some mind-bending findings of both the psychological impact of adverts and their sheer quantity in our lives.

The authors then take us in detail through the tortuous tale of how, in the UK and then elsewhere, over the 60 years roughly corresponding to my own lifetime, tobacco advertising finally came to be banned. Remember ASH, the health campaigners? And FOREST, the deceptively-named pro-smoking lobby? They and many others feature here, and in the book’s comprehensive index.

The upshot of all this activity, we are reminded, has been a dramatic reduction in smoking both here in the UK and in most of the western world.

Why, then, not apply what we have learned from tobacco to some more recent bad habits that we have fallen into – like buying obese vehicles to drive around in, or flying too often? This, after all, isn’t going to stop us from indulging: instead, it will relieve us of that nagging feeling that we are somehow ‘missing out’ if we don’t – which is the basic premise of every advert.

My only beef with ‘Badvertising’ is that in places you can feel the writers’ haste to get all this down on the page as soon as possible! This shows up particularly in the chapter about the sponsorship of sport, where the thread flips back and forth between listing which sports the high-polluting industries sponsor, and going into technical detail about what damage (not to the sport, but to health and society in general) they do. But perhaps it was just me.

Where this book really shines is in the final chapter. ‘A World Without Advertising’ sounds utterly fantastical, right? Well, er, wrong! It is so well within the realms of the possible, nay, the absolutely-easy, that many places have ‘taken down the billboards’ (and by the way it has taken this long for that Ogden Nash quote to appear) and benefitted as a result. In a refreshing change for an eco-campaigning premise, ‘Badvertising’ is not asking for the Moon with Brass Knobs on: merely for one straightforward piece of legislation.

I recommend ‘Badvertising’, firstly to people looking for a simple but effective step that we can take to help our beleagered environment and our quality of life, and secondly to anyone who has ever seen an advert and wishes to look after their brain.

View all my reviews

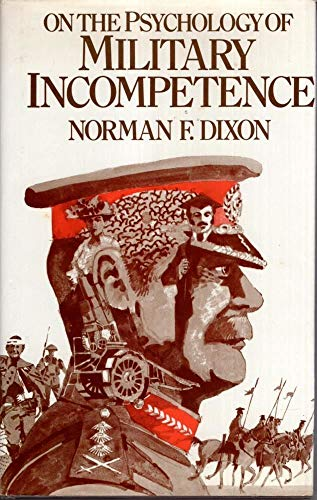

Book review: ‘On the Psychology of Military Incompetence’ by Norman Dixon

On the Psychology of Military Incompetence by Norman F. Dixon

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

At times like these, here in Europe at least, questions on how battles – and wars – are won or lost are existential. What do we need, in order to save ourselves?

It’s too tempting to reduce the question to just considering which side can get hold of the larger amount of energy – food and fuel for fighters and other citizens alike, energy to keep warm (or cool), and kinetic energy, in the form of ammunition, to throw at the foe.

This book is for people who want the whole story: the human factors which can make the crucial difference.

The author first takes us on a tour of some of the most well-known and notorious instances of incompetent military leadership: from the initial battles of the Crimean War, with British troops put ashore with neither shelter nor food in the teeth of ice-cold driving rain, through a century of catastrophic mismanagement, to Arnhem, where a single file of tanks on a narrow, raised road across 60 miles of boggy ground (ring any bells?) failed to reach their appointed place in the consequentially-unsuccessful Operation Market Garden.

After dismissing the popular explanation of straightforward stupidity as a factor (many of the leaders of disasters had other, successful, campaigns under their belts), we are left with, as the author puts it, ‘a case to answer’.

This ‘case’ takes us through a menu of psychological factors common to people who are attracted to, and who are good at getting promoted in, a military environment – but which then place them in an impossible position: the very qualities that got them to the top prove a liability when it comes to leading squads of real humans to perform unnatural feats in conditions of extreme stress.

Why, then, isn’t military incompetence more rife? And why, also, did the side on which Britain fought go on to win both the wars just mentioned? In some ways these two questions answer each other: we read on to find out about the psychological factors which rendered the opposition’s leaders in these two conflicts even more incompetent than our own!

But isn’t all this something of an insult to the majority military leaders who, under extraordinary stress and danger, nevertheless pull off incredible feats of leadership and bravery? Well, the author asks us not to take it as such. He wants, more than anything, to solve a problem, and stresses that in spite of all the psychological factors we explore with him, the incompetence is the exception rather than the rule.

As he delightfully puts it, devotees of the military should no more take offence at an analysis of one of the reasons why things can go wrong, as should “admirers of teeth complain about a book on dental caries”.

And what of this constellation of factors which come together to make for incompetent military leaders? Many of them can be seen all over the world, but some are uniquely British.

These latter – although this book was written nearly half a century ago now – still plague us on these islands. And I don’t mean among the military.

I’m a lifelong civilian, and a physicist rather than a psychologist or historian. And yet I found this read fascinating, and in places hauntingly familiar. Anybody, in the end, who has even the remotest interest in why they have ended up labouring under poor leadership, in Britain or elsewhere, would do well to read this book.

View all my reviews

New adventure!

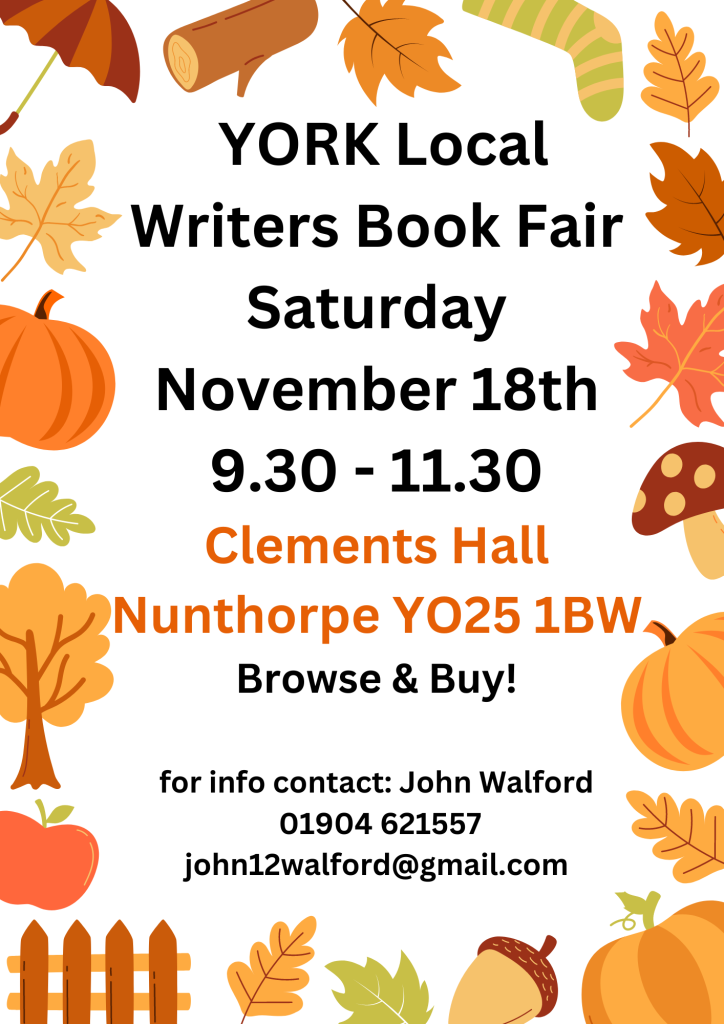

Book Fair in York this Saturday!

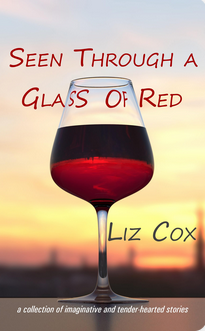

Book Review: ‘Seen through a glass of Red’ by Liz Cox

Seen Through a Glass of Red by Liz Cox

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I was immediately intrigued by the charming title. It promises slightly offbeat or surreal household or family dramas, and it doesn’t disappoint.

Characters, sympathetically drawn, wrestle with everything from a desire to spend a cosy Christmas alone, to a fraught night vigil following efforts to save the life of a son gored in a hunt (no spoilers).

In simple, sometimes even too pedestrian, prose, there are charmingly-drawn cafes with interesting meetings and conversations. There are feelings of belonging, but sometimes of quiet desire to ‘move on’. There are a lot of scarves. And nice shops.

And one, big, gut-wrench.

Some of the stories have the same sideways look at the otherwise-ordinary that I recall from David Sidaris’ ‘Dress your Family in Corduroy and Denim,’ but with a little more myth and ‘weird’.

The subtle weirdness of the collection is heightened by the number of anachronisms. You never know what decade you are in. A War Widow – we assume WWII, since her fiancé is mentioned as leaving for ‘the front’ – must be jumping out of bed and walking briskly to the park to buy croissants at nearly a hundred years of age. An encounter takes place in a train with compartments – I can’t remember the last time I saw one of those. There’s a restaurant kitchen whose young staff are devoid of phones with Google for urgently locating a recipe, and finally the eeriest of all: there’s the moon travelling the wrong way round the earth.

Is that last one deliberate? Given that in this particular tale an entire landscape has materialised and then just as mysteriously disappeared overnight, who knows?

View all my reviews

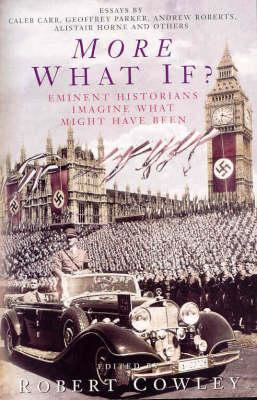

Book review: ‘More What if’ by Robert Cowley

More What If? Eminent Historians Imagine What Might Have Been by Robert Cowley

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Now then.

It appears I was ‘a bit previous’ in my review of the first ‘What If’ volume of alternative historical possibilities, giving it 4 rather than 5 stars for, among other reasons, lack of my favourite ‘what-if’ of all history. I find the sequel has, as its first line of back page blurb,

“What if, on 14th October 1066, William the Conqueror had lost the Battle of Hastings?”

No spoilers here, but a ‘fun fact’ – which I hadn’t known until my research, during the writing of ‘The Evening Lands‘, on the Battle of Fulford (the first of the three 1066 battles, and which happened just down the road from where I live) – is that Harold Godwinson owed his religious allegiance to Constantinople – not Rome. The England invaded by William was, technically, an Orthodox Christian country, and part of a sweep of civilisation extending not just through Viking Scandinavia (“As every schoolkid knows”) but also as far east as Kyiv and Novgorod – the latter at that time building an intelligent effort to “Seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to law.” What might have happened if that sweep of Northern civilisation, rather than the Rome-based one of southern Europe, had held sway over the Middle Ages?

Uh, so, right – this is a book review not a soap-box. To horse!

A wider range of ‘What if’s are covered here, not just the military. The effect upon Western philosophy of Socrates dying in battle (yes, he had to do National Service); Pilate sparing Jesus (so no crosses on necklaces); Ming Dynasty Chinese navigator Zheng He making it all the way round the Cape of Good Hope in his giant ships instead of being called back home…

‘More What If’ lacks the short-and-sweet inter-chapter essays of the first volume, jewels which included some of the most extreme, rapid, and breathtaking turning points. But it lives up to its name even better than the first volume in that there is a little less concentration on the minutiae of battle and more on the speculation of the wider results.

Like the first ‘What If’ it is quite information-dense – worth a pause after reading each chapter especially if, like me, you’re not an historian. Both books are also a pretty good way of understanding what actually did happen on all the world-turning occasions they describe.

So it’s getting more stars than volume 1 – and not just because of Hastings.

View all my reviews

Book review: ‘Were you still up for Portillo’ by Brian Cathcart

Were You Still Up for Portillo by Brian Cathcart

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Want to revisit the glory days of the biggest defeat of the Tories since… well, ever? This is your read, and Brian Cathcart, telling it in straightforward journalistic prose, is your man.

The strapline ‘re-live the drama of election night hour by hour’ describes exactly what this short (188 pages), information-dense volume will do for you. I read it, literally, in one night, starting at about 10 and finishing before 2 – in other words almost in phase with the night itself. And honestly it took me right back there because, on the night in question (1st-2nd May 1997) I was, like the title, “up for Portillo” and his magnificent defeat by the young, as-yet-unknown Mr Twigg and his mischievous grin (there are pictures).

Each chapter covers one hour, starting from the commentariat’s no-man’s-land of close of polls at 10 pm, when no results can possibly yet be in but pundits and psephologists are asked, relentlessly, to offer opinions on how the night will unfold. The studio set-up, both BBC and ITV, and the awkwardness, are captured in loving detail. Stung by their 1992 defeat after the polls had promised victory, Labour spokespeople forced themselves to remain reserved, while pollsters of other persuasions and none were little better off.

The ‘race to be first to declare’ had, by 1997, become a thing, and Sunderland South’s military-style operation is described in detail – they declared within 46 minutes, setting a record. This may have been the election where Chris Mullin, ther resulting first-elected MP (and author of a novel called ‘A Very British Coup’, which by the way I highly recommend) pointed out that he could now enact some ‘intersting’ legislation by voting it through a House in which he was the only sitting MP.

Hour by hour we are then taken through the night’s extraordinary events as MPs, including no fewer than seven Cabinet ministers, lose their seats to young, diverse, and often surprised, Labour and LibDem adversaries. Want to refresh your memory about Jonathan Aitken’s ‘sword of truth and trusty shield of fair play’, Martin Bell ‘The Man in White’ (and the record he set), or Chris Hamilton and his alleged Brown Envelopes? It’s all here, in precise but passionate detail, along with the unfolding tally of newly-minted Labour and LibDem seats, each accompanied by its ‘target number’ – for example ‘1’ being the seat with the slimmest Tory majority over Labour, and therefore the easiest for them to claim. Target numbers up to the 190s get a mention.

The two almost throwaway quotes I personally recall from the night both get a mention. “Hove? Hang on – something seismic must be going on if they’ve lost Hove…” (I used to live there), and “Well”, (addressed to Cecil Parkinson, Conservative party chair), “You’re head of a fertiliser company: How deep in it do you think you are now?”

In the end, this is the story of a dawn that came after a long night. Eighteen years of Tory government had made the economy’s headline numbers look good, but at a terrible cost. Individual failings of ministers and MPs – adultery (after the obligatory ‘family values’ speech), bullying, and financial shenanigans, added to the country’s woes of widening inequality. The Great British Public had simply had enough. The exact reasons for the dramatic scale of the defeat are not probed in detail, bar a few quotes from MPs. However I like to think that our human sense of fair play remains – that in these times of even further widening of inequality, to the extent that life is beginning to be made impossible for some, the British public will shortly send our current crop of Tory MPs, whose dirty dealings make the class of ’97 look like rank amateurs, away from anywhere near the levers of power.

View all my reviews

Book review: Payback – Debt and the shadow side of wealth, by Margaret Atwood

Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth by Margaret Atwood

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

“Lovely weather we’re having today!”

“Aye. We’ll pay for it later.”

Within these scant few words lurk every functioning human being’s sense of fairness – of balance – of the idea of debt. An idea which, recent experiments have demonstrated, is older than humanity itself.

This short but action-packed read won’t get you out of debt, nor shed much light on the machinations of High Finance, newly lain bare at the time of its publication in 2008. What it does, in Margaret Atwood’s glittering prose, is detail the place of debt in our culture: in mythology, in religion, in crime.

We start with origins: stories of primal debt (are each of us in debt for our very existence?), of genetics (can our nearest genetic neighbours appreciate the idea of debt? Spoiler: they can!), and of ancient myths of blood feud and balance.

From there the reader is taken on a tour of the many ways debt and sin have been seen as equivalents: the criminal who, on emerging from jail into the bright light of day having ‘paid his debt to society’ being the most obvious – but weird if you come to think of it – example. How has society actually benefitted from his incarceration? What has he paid us? This debt is all but inpossible to quantify, yet the crossover between financial debt and sin has worked its way into our very language. ‘Amends’, ‘Redeem’; ‘Saviour’.

We now turn to Atwood’s home turf: story. In a way, every debt is a story. It has a beginning (how did I get into debt?), a middle (how do I cope with it, and how does that change me?) and an end (Do I get out of it? If so, how? And if not, what are the consequences?) And why is it so dangerous to be a Miller’s daughter?

Of course Dr Faustus and Ebenezer Scrooge turn up at this point. In fact Scrooge plays quite a major part, by in a way subverting the debtor’s story. Debt is about deadlines, and Scrooge has his deadline extended by a vital 48 hours – time to see the error of his ways.

The final chapter brings Scrooge’s tale right up to the present. Who is this miscreant’s equivalent today? What is he doing, how does it harm the rest of us, and how can he ‘redeem himself’?

In just 200 pages (plus notes, bibliography and index), this book packs fascinating detail, some of which even I hadn’t come across during my research in the writing of ‘The Price of Time’.

Two things it could be said to underplay are the racial aspect of debt (Clifford’s tower, scene of the debt-driven massacre of York’s Jewish population, is within walking distance of where I live), and a contemplation of the effect of time on debt: debts of finance, unlike debts of misbehaviour, in our society increase exponentially with time, giving them a life of their own. A life whose story – and whose evil – we underestimate at our peril.

View all my reviews

Book review: ‘What If?’ edited by Robert Cowley

What If?: The World’s Foremost Historians Imagine What Might Have Been by Robert Cowley

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Have you heard the one about Winston Churchill and the New York taxicab driver? Could wild west sharp-shooter Annie Oakley have prevented World War One? And might the refined culture of Ancient Greece have been stopped before it started by… one man’s failure to get a good night’s sleep?

At a time like now, when history seems at a turning point, it’s fascinating to look back on so many other moments when a tiny change in events – weather, ship maintenance, one narrowly-avoided death… – might have changed the course of our past, and with it our present.

“What if..?” assembles the expertise of 20 military historians to ponder such turning points. Each essay sets the scene – culture, people, events – in detail before zooming-in on the point of change where things might have happened differently. These alternative chains of events then unfold with realistic logic and we get to see the result – sometimes a completely unexpected transformation, and a few times very little, or very subtle, change.

The turning-point that punched me in the guts had to be the one that spared Western Europe from the Golden Horde. I came to appreciate what had been lost: enlightened city-states in what is now Russia; irrigation systems that enabled the arid Middle East to support millions (also in enlightened city-states). The technology, and the entire population who might have remembered how to rebuild, were simply wiped off the map. We still don’t have the knowledge to rebuild! It could be said that Russia and the Middle East are living with the consequences to this day. Russia were having to ‘pay gifts’ to the Mongols’ descendents until Peter the Great finally put a stop to it – in 1700, after some 450 years of damage. “When I recall the beauty of our history before the accursed Mongols I want to drop on the ground and roll around in despair,” wrote Ivan Bunin.

Even now, the Chinese unit of paper money bears the name of the Mongol ‘dynasty’ there – Yuan.

So after all that, why only 4 stars and not 5?

It’s personal to me, as a Yorkshirewoman. I’d love to have had a chapter included on what would have happened here had William failed at Hastings. Our region would not have been massacred (three quarters of our population perished) nor its seat of government destroyed. Feudalism as we knew it would never have established here and, most bizarrely, England might have remained ‘Orthodox’ – answering to Constantinople and not Rome.

But we are all accidents of history, so 4 stars it is.

View all my reviews

Book review: ‘Entangled Life’ by Merlin Sheldrake

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

“They are eating rock, making soil… nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions…manipulating animal behaviour, and changing the composition of the earth’s atmosphere.”

And yet, as Merlin Sheldrake (and what a superb name for someone writing about things with such apparently magical properties) points out, we do not even have university departments studying this ‘third kingdom’ while zoologists and botanists are busy researching the other two.

What is it like to be a fungus – to have your consciousness ‘distributed’ through a network rather than centralised in a brain with inputs from the familiar senses? Where do you – as (for example) a forest floor fungus – end, and the plant roots with which you are conspiring begin? Why did it take our Sciences so long to get our heads round the idea of ‘symbiosis’, and should we now be going beyond the simple discription of a conspiracy between two different forms of life to a more holistic approach?

Sheldrake takes us from a sensual hunt for truffles in the forests of Italy, via a description of the life of a mycelium (they can actually communicate the ‘shape’ of their environment to help them grow towards food, for example), to the story of their evolution as the first life on land – busy breaking up rocks before plants arrived to conspire with them in an exchange of nutrients, as they still do today. Fungi even provide the food for a plant who ‘cheats’ – the white leaves no longer bother with the expensive fabrication of chlorophyl for photosynthesis because the plant taps the underlying fungal network for its food.

Fungi can evolve to break down and render harmless the most vicious organic toxins – the dreaded Glyphosate, for example. They can also do terrifying things to ants – but then again, since they can alter minds, are the ants too stoned to feel the pain, or care? And what about what they do to the minds of people?

All this is just a taster of the content of this fascinating, information-dense story, written by someone obviously at the top of their subject, both by profession and by passion. Not being a life scientist myself, I found it worth stopping at the end of each chapter simply to allow my mind to take it all in.

I was curious that, apparently only some three quarters the way through the pages, the story began to ‘zoom out’ and become more philosophical. Then suddenly I cam to the denouement (if you can have such a thing, with fungi) – the remaining pages form a comprehensive bibliography and index.

I recommend this book for anyone interested in life and how it functions. Learning about animals and plants is great, but without knowning something of the other kingdom that lurks, links, conspires and quietly directs, no knowledge of life in all its glory is complete.

View all my reviews